This “I” we each inherit, made spine

of the world, axis, pole,

look-out from the world’s helm

gazing on the universe,

gazing on you,

gazing on death…

“Mummy,” I said,

seven or eight years old,

“I have decided

that I am God.”

We were walking east

along Glebe Road

towards the shops on Upper Mulgrave,

my right hand held in her left.

“Oh, what makes you say

a thing like that, dear ? How

can you think that you are God ?”

“Because I draw

everyone’s eyes, somehow,

towards me. It can only mean that they

know that I am God. And then I close

my eyes and they

just disappear. Further proof, you see,

my mother,

that I am God.”

My mother’s mind –

destined in her last years to shrink

and leave her

speechless and helpless in her bed –

had been engaged, just then, on other concerns

than holding hands with God.

“Surely it just means

that their eyes are idly resting on you

while their attention wanders

down secret avenues

miles away,” she said. “And, my son,

it is quite enough for me that you

are just you,” she added.

“Just me ?” I felt let down.

I and all those other people knew

quite well that I was God.

Yet my own beloved

mother refused to recognise

who it was here walking at her side

eastward along Glebe Road

aiming for Upper Malgrave.

“There’s no such thing as ‘just me,’

I said to myself. “‘Just‘ means nobody.

I am I.

‘I’ means God.”

Rogan Wolf, July 2020

The poem’s story is true, as best I can remember it. I wonder how my mother felt.

And I think I’m talking psychology here, or what is often called “human development.”

At the time described by the poem, I was clearly old enough to have become dimly aware of some of the momentous issues and questions that surround us all and I was trying to make sense of them. And my conclusion on this one, the wonder and miracle of Selfhood and the mystery and difficulty of its relationship with Other, seemed the only logical one available.

How else to make sense of my growing inwardness, the wild and shadowy world of it, all my own, as compared to, and surrounded by, all these other living forms, so powerful in their different ways, many looking a bit like me, but never of me, always outside of me, and outward in themselves to me, coming out of the world, at me ?

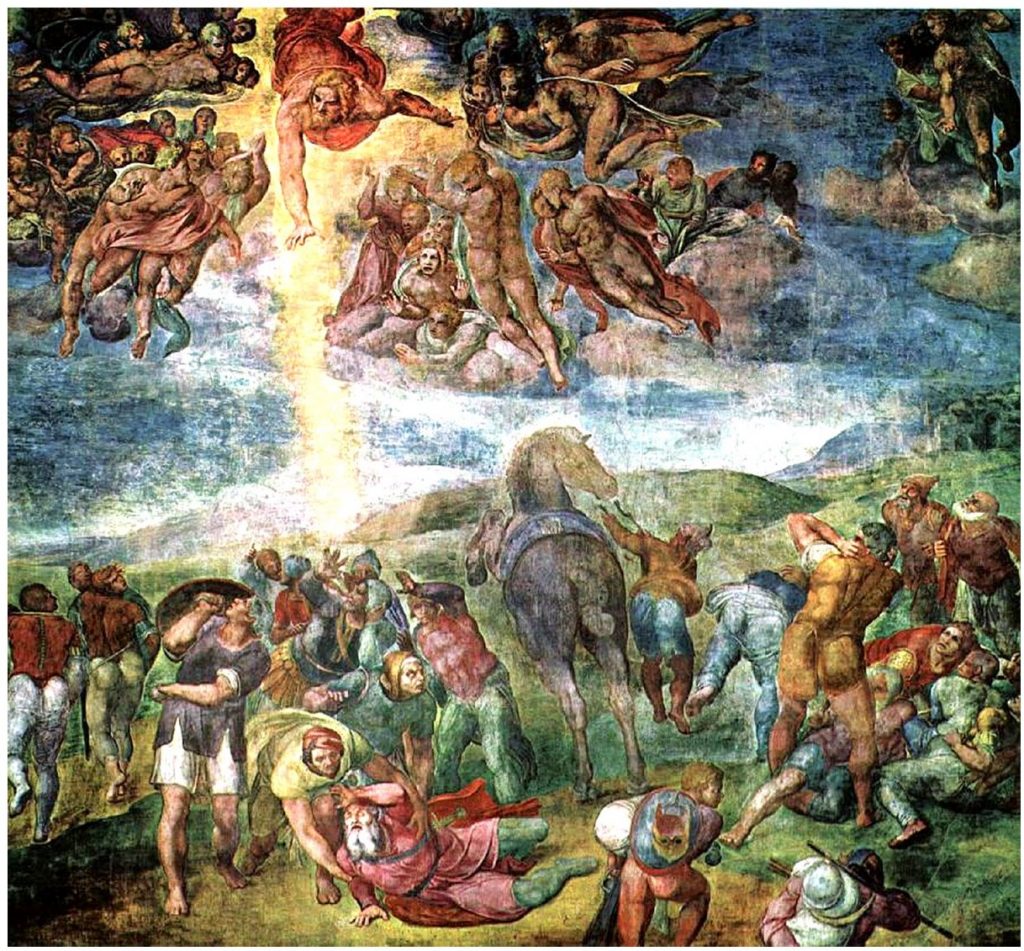

But then at some point, you move past that child’s position which assumes “I” is essentially different and singular, pole of the universe, surrounded by the world and, beyond that, by the universe ; you reach past that child’s delusion (and terror ?) of omnipotence and realise – whatever the word “realise” really means – that the universe did not appoint you as its single and central pole and axis. Everyone you meet, even every thing you meet, is as much pole of the universe as you are, and all look out at you, just as you look out at them. As they might seem your objects, so you might be theirs.

It is thus the case and the fact that you, and all else outside of me, matter as much as I do. That is the adult fact of the matter. As I matter, so do you. We are members one of another. That is the fact. Anything else is delusion, a retreat from the wonderment and bewilderment of reality.

But how on earth do you get to that adult position from the one experienced on Glebe Road, aged seven or eight ? And do you really arrive there by a certain age, and then stay there ? And do we all get there, or do some of us never arrive ? And if it turns out to be too difficult to stay solidly and consistently in this adult state of awareness of reality, how much of each day do most of us spend in a state of retreat and relapse into the ego-centric child’s delusional world-view ?

I am no Christian. I do not “believe” the tenets of the creed which those shrinking congregations speak together during their age-old assemblies. For instance, I have no doubt but that death is final and complete. And I cannot, and have no need to, believe that Jesus Christ was conceived by any process other than the usual human one. And I cannot, and have no need to, believe that the stone literally rolled away and he was literally resurrected. I do not associate myself with this or any other formal religion, or belief system. But neither can I deny that when I take part in Christian liturgy worthily conveyed, I respond with a deep sense that what I am hearing, is closer to human reality and our condition than anything else I hear in my life as I go about it in our present times. The standards, priorities and insights being articulated here are right in their essence. The images are accurately evocative, more accurate than anything else I encounter. The essential vision seeking expression here is the truth and is still radical and profoundly questioning. Holy is real, here. And this air of reverence is apt and good to breathe..

But I have trouble with the Christian use of the word “love.” It has too much human history trailing after it, weakening it. Too many instances of hypocrisy. Too strong an association with mere self-righteousness and the repression of true emotion, a drawing back from passion. Too strong an association, too, with a mere cuddly personal feeling, a limp mildness. You don’t need a halo, or a cowl, to look reality in the face.

I put more faith in cooler words than “love.” Words like “recognition” or “realisation.” That state of awakeness reached when you see and begin to act in recognition of the fact and reality that I am not the only centre of the universe, that you and all else outside of me matter as much as I do.

I even presume to think that this is contained in the shadow, maybe even the kernel, of St Paul’s majestic words in the First Epistle to the Corinthians, chapter 13, ending : “…And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity.” (Authorised (King James) version).

The Latin for charity is “caritas” although it can also be translated as love and most present translations follow the latter reading. And the New Testament was originally written in Greek and the word Paul actually wrote was apparently agapē (ἀγάπη) meaning a personal, passionate form of love. The love a parent might have for his/her child, as for someone infinitely precious, closely connected in flesh, blood and spirit.

So I am on shaky ground here, in questioning this word “love”. But being a parent does not require you to be blinded one day along the road, or wear a dog collar or a halo, to be “holy.” It does not need you to be meek, or passionless, or “pure.” It does, however, need you to be reasonably adult and to be able to treasure, appropriately, a life that relies for a viable future on your nurturing and recognition and loyalty.

So the eight year old who thought that he was God, as the only way he could explain to himself the mystery and wonder and immeasurable preciousness of selfhood, learned later than everyone else has the same experience, and is as central as he. He may shut his eyes as often as he likes ; in truth, those other people don’t disappear. That step, from delusion into realisation, was a momentous one and I think it took me a while. I think quite possibly, in fact, I am still taking it. When I have finished taking it, I shall become an adult.

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child : but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

“For now we see through a glass, darkly ; but then face to face : now I know in part ; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”

To deny the preciousness, the equal centrality, of those around you, those “Others,” is to deny the truth and reality of your own preciousness. It is the infinite preciousness of our plain, shared, endangered reality.